Summary & Takeaways

You might want to set goals or resolutions, particularly as a new year approaches. The problem is that these terms are misunderstood and misapplied. Your real Goal is to get the most of what you value out of your life. To do that, you need to have a system that helps you to methodically and compoundingly evolve yourself into a person who makes decisions that are in ever-growing harmony with the way you want to live.

This essay is not about constant quantified monitoring of discrete resolutions. Rather, it lays out a framework that enables you to 1) grow your awareness of what you truly, deeply care about (your “values”), 2) develop an approach to shift an ever-increasing portion of your decisions to be in ever-closer alignment with those values, and 3) pursue the best life you can, subject to your limited time and energy.

This essay first outlines a logical theoretical framework to unify the various terms involved with “goals” in the context of having the best life you can have. Second, it lays out a practical approach for applying this framework.

Theoretical Discussion: A Unified Way To Think About Goals

Existing Terminology & Approaches to Goal-Setting Are Not Logically Cohesive

There are a large number of terms that are related to “goals” – among many others, these include “resolutions,” “habit-stacking,” “values,” ““metrics,” and of course “goals.” There are an even larger number of approaches related to annual processes in which these terms get put to practice. Ultimately, all are intended to help you get what you want out of life, but are nebulously defined and not unified.

Most of These Terms Do Not Start at the Actual Starting Line For The Problem They Intend To Solve

The starting line can be found with a question: why are you interested in having resolutions or setting goals in the first place?

For illustration – perhaps one of your “resolutions” is to “lose weight.” Well, why is that? To be in better physical shape. And why do you want to be in better physical shape? To be healthier. Why do you want to be healthier?

Because you want to have the best life you can, of course! And that – your desire to have the best life you can – is the correct place to start1

The Maximization Equation For Your Capital G “Goal”

Now that we know what you are really aiming for when you make resolutions or goals (to have the best life you can) – the question is what does that really mean?

I find the following thought exercise to be helpful. The best life is the one that you would not trade for another one (with perfect information). The best life is thus the one that you get the most out of (or “maximize”), because if you could get more out of life in another life, you would always trade for that one.

Having further refined the quest – the question now becomes – how do you go about getting the most out of life?

Getting the most out of your life is equivalent to maximizing what you place value on. The key to getting the most out of life, and thus having the best life you can, is to maximize what you value. Having a life that maximizes your values is “The Capital G Goal”

But There Are Constraints On This Maximum

In an ideal world with no constraints, you would be able to live your life to maximize what you value without conflict or reconciliation across those values.

Unfortunately, as humans we must make tradeoffs. These tradeoffs are the result of three limitations imposed from physics-level / biological-level constraints:

- We have limited time2

- We have limited energy3

- We only control a subset of the things in our life as we live in a multi-agent world full of exogenous and uncontrollable factors.4

The first two are (to some extent) controllables, and are the focus as it relates to what you pursue (because it is not worth spending time attempting to optimize non-controllables). It is up to you to allocate each of your time and your energy across the various things you wish to pursue5. Your objective is to allocate these as efficiently as possible to maximize what you value6.

You are forced to make tradeoffs due to these constraints through what we all know as “decisions”. Decisions are the base layer transaction of your life through which you allocate your time and energy. You make hundreds of them every day – some deliberate, some instinctual7. A business on its income statement reports “revenue,” but that revenue is the sum of thousands of individual sale transactions as the base layer8. The base transaction layer of life is decisions. The sum of your decisions is (the controllable portion of) your life.

Now That We Started From the Starting Line, We Are Halfway and Can Talk About Goals. But First Let’s Recap

The reason you want to set resolutions / goals is that you want the best life you can have, which means getting the most out of your life, which means living a life that gets you the most of what you value. BUT you are faced by three constraints, 1) you don’t control everything, 2) you have limited time, and 3) you have limited energy. What you want and the (controllable) constraints you face intersect in the form of tradeoffs when you make “decisions.”9

Perhaps you make a “resolution” to see your friends more. But your friends frequently meet for drinks, which go late; if you join you might not be able to run the next morning, which interferes with your resolution about exercising every morning. How do you make the best decisions?

Values Are The Highest Level Grading Rubic For Making Decisions Aligned With What You Want

What you really need is to establish a framework for making the best decisions. You need that framework to be a standardized grading rubric and also to be broadly applicable to a wide range of decisions so that you can evaluate how options compare against it when you make decisions. This framework is your values.

Your values are core desires that are likely largely consistent year-over-year. They are likely fairly fundamental. They might look like they belong on Maslov’s Hierarchy of Needs. It is unlikely you have more than 5-10 values. Examples of values are “deep friendships,” “family connectivity,” “physical health,” “financial security,” “intellectual curiosity,” “truth.” These are your north star, and everything else is downstream from them if you want to optimize your limited time and energy to get the most out of your life.

Throughout the rest of this post, we’ll run through an illustration (in italics) to help clarify as we go. Perhaps your values are deep friendships, physical health, family connectivity, financial health, being present, and intellectual curiosity.

Values are powerful because they sit at a layer of abstraction that lets them be broad-reaching and widely applicable in your life. They’re a grading rubric that you can use across all decisions, not just some subset. But therein also lies their limitation – sitting at such a high layer of abstraction also limits their usefulness in daily decision-making because it requires significant time and energy to make a decision at the layer of comparing across values. You simply cannot use this process to make every decision in your life.

Perhaps it is Friday night. You have plans with friends, are behind on sleep, want to run the next morning, and have a toast to write for your Mom’s birthday coming up next week; you may value each of “deep friendships,” “physical health,” and “family connectivity” – but it is going to take a lot of time and mental energy make a grid for how these options varyingly impact those values and thus to make your decision.

Goals Help You Move Down A Layer of Abstraction

That’s where “lower case g” goals come in. These are what you often think of as goals. Goals sit at a layer of abstraction below values and are easier to translate with when making a decision. Goals include “lose weight,” “see my friends more,” “become closer with my aging parents,” “run a marathon,” “get a new job.” A goal is an aspiration that can help you on your way to living in accordance with your values (which can be a bit harder to see in the day-to-day). Goals change over time, as the way to best live in accordance with your values does.

The benefit of goals is that they make values more concrete for the current time and circumstances of your life. They are more cognitively digestible than values (“become closer with my aging parents” is tangible and relevant at your current life stage, while “Family Connectivity” is abstract and something you generally desire across the entirety of your entire life). As a result, goals are more tangible and motivating mile-markers that help you more closely live your life in line with what you value.

The key reason that goals are helpful is that if you have aligned your goals with your values, then you can use goals via a sort of transitive property to make decisions. Instead of having to go all the way to your values when making a decision, you can see how things align with your goals. Your goals are like the TSA Pre-Check line for decision-making, and as a result they save you time and energy.

But while having a goal to “become closer with my aging parents” can help you in making a decision across options, it is not an actual action you take. As an example “becoming closer with my aging parents” isn’t something that you actually do – spending high-quality time with them is something you do; inviting them on your vacation is something you do; having difficult conversations if they are needed is something that you do.

Actions Are How Decisions Come to Life

That is where targeted actions come in. Decisions leave the theoretical world and enter physical reality in the form of an action. Actions are things that you do and that you specifically exhibit direct control over completing. The way to test if you have arrived at the action layer of abstraction is by asking “is this a thing I can simply go “do”?” You can’t just go “become closer with your aging mom” – but you can for instance establish the habit of calling her on your walk from the subway to your office, or by taking the discrete action of going on a trip with her to visit where her side of the family is from.

As it relates to goal-setting, actions are of course about targeted / intended actions – meaning things you are planning or desire to do, in support of your goals and values. There are two broad categories of them: Discrete Actions and Habits.

Discrete Actions are one-time in nature (e.g. “Throw my Mom a 70th birthday party where I give a speech to all her friends about how amazing she is”; “‘go on a trip with my Mom to understand our family history”).

Habits are repeated in nature (e.g. “Call my Mom every morning on my way to work”). Habits possess a number of special properties – they convert more of your decisions into system 1 thinking, they take advantage of compounding, and they leverage opt out vs. opt in inertia to your benefit if developed thoughtfully10. Habits have super-powers and are lethally efficient with your constrained time and energy. As a result, having habits that are aligned vs. unaligned with your values (a better way of saying “good” vs “bad” habits) is one of the biggest determinants of you having the best life you can.

Values, Goals, and Actions (Discrete + Habits) Serve as Different Layers of Abstraction For the Same Common Aim – Helping You Get What You Want Out of Your Life

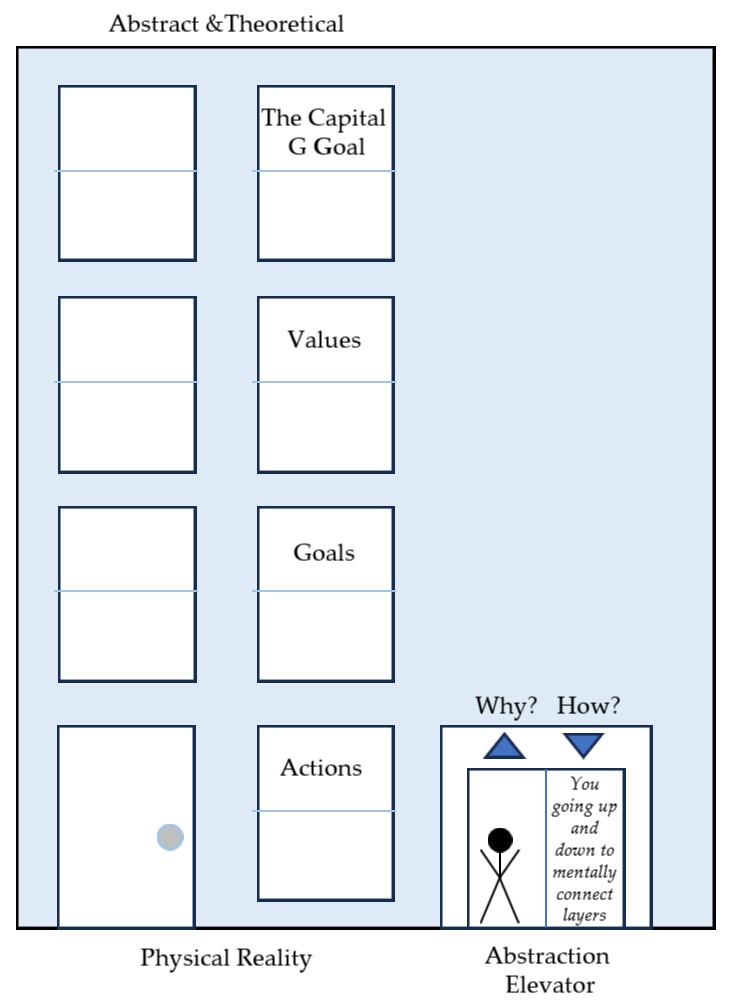

To visually connect these terms, I like to picture an “abstraction elevator” in a four-story building, with each floor getting more theoretical and removed from the world of atoms as it goes higher. The penthouse is “the Capital G Goal”; the third floor is your Values, the second floor is your goals, and the first floor is where your actions bring decisions to life. The way you move up and down floors in the abstraction elevator is as simple as pressing a button: “why” for up and “how” for down. The abstraction elevator is a framework to help you more tightly and efficiently draw connections in your brain between various abstract values and goals and the specific actions you need to take to support them. By doing this, it helps you make better decisions.

Perhaps you find yourself the weekend before your mom’s 70th birthday party you planned; the party is ready, but your speech is not. You have plans with friends, and even if you skip them, you will be up late to finish the speech. You decide to write the speech. It’s now 3 o’clock in the morning and you wonder to yourself: “why am I doing all this again?”

You’ve pressed the button in the elevator and are moving up to the second floor from the ground level. You’re doing this because one of your goals is to “become closer with my aging parents”. You ask yourself – “why do I care about this goal again?” and find yourself moving up to the third floor. Indeed, the reason this is one of your goals is because you value “family connectivity,” and the goal of “become closer with my aging parents” is a way to make that value more concrete in an applied way for your current phase of life. “And why does that value matter again?” you ask. You head up to the penthouse – because your capital G Goal is to have the best life you can. You then ask yourself – okay but how do I do that? You find yourself moving back down…encountering the various things you value.

You may have noticed that on the second floor you encountered a tradeoff. One of your goals was indeed to become closer to your aging parents, but you also wanted to socialize more with friends (which going to a bar would help with) and wanted to be healthy (which not sleeping well doesn’t help with). Facing the constraints you have on your time, you made a decision to prioritize the goal related to your parents because you logically concluded that you have many opportunities to see your friends at a bar and many nights of sleep, but there is only one opportunity for your mom’s 70th birthday and it is not clear if she will make it to her 80th.

Each Floor of the Abstraction Elevator Has Pros & Cons; Collectively They Let You Use the Transitive Property to Maximize Efficiency with Your Time & Energy

Values sit at a level of abstraction that makes them universally applicable and great for understanding what you want out of your life at the highest level, but it also means that they require substantial system 1 thinking (which requires a lot of time and energy) to make most decisions. You do not have enough time and energy to think about your values for every decision.

Goals are more crystalized and concrete than values. This means that they are not universally applicable, but it lets them be more tangible and motivating; critically, goals enable you to take advantage of the transitive property to make efficient use of time and energy. If you have aligned your goals with your values, then if something aligns with a goal, it most likely aligns with your values.

Actions are the most concrete because they are literally what you do. This means that they are not applicable beyond their immediate use case (and thus limited in their breadth) but are the ultimate way that decisions meet physical reality.

Together, the various layers in this framework are intended to do one thing: help you get the best life you can, subject to the limited time and energy that you have. This framework works by helping you establish what you truly care about, and then taking advantage of various mental hacks for time and energy savings to help you make continuous progress in uniting your actions with the things that you value.

Departing Remarks on The Risk With “Goals”; What this Framework is Not and What it Is

The risk with all of this is that you lose sight of the fact that a goal or habit or discrete action is a short-term goalpost and start thinking about it as the end in and of itself. It is important to remember these are not the end, but a means to the end. The “end” is simply aligning yourself closer and closer with what you value, not some marathon time, amount of money, career achievement, etc.

The capital G Goal is to have the best life. Focusing too much on tasks, checkboxes, and quantification can consume a great deal of time and energy, crowding out the actual experience of living. The framework here is intended to help you live deliberately in a way that lets you get the most out of life comprehensively, but if the process of doing this becomes all-consuming, you are ultimately missing out on being present (which is a multiplication function on time and thus should likely be a value for everyone11). If pursuing this (or any other) framework comes at the cost of being able to be present due to incessant tracking of progress on goals and habits, then it is counterproductive to its purpose.

To round out the theoretical framework, it is worth revisiting where this essay started. This framework is not about constant monitoring of “goals.” It is, on the other hand, about “growth12.” The intention from this is to 1) grow your awareness of what you truly, deeply care about (your “values”), 2) take advantage of time & energy hacks to help you subconsciously and intuitively grow an ever-increasing portion of your decisions to be in ever-closer alignment with those values, and 3) as a result, live the best life you can have subject to your limited time and energy. It is about bringing the decisions you make and the way you live into ever-growing harmony with the way you want to live. It is about becoming a person who intuitively makes decisions that are aligned with your values.

Practical Application: Using This Approach

What This Framework is Intended to Do For You In Practice

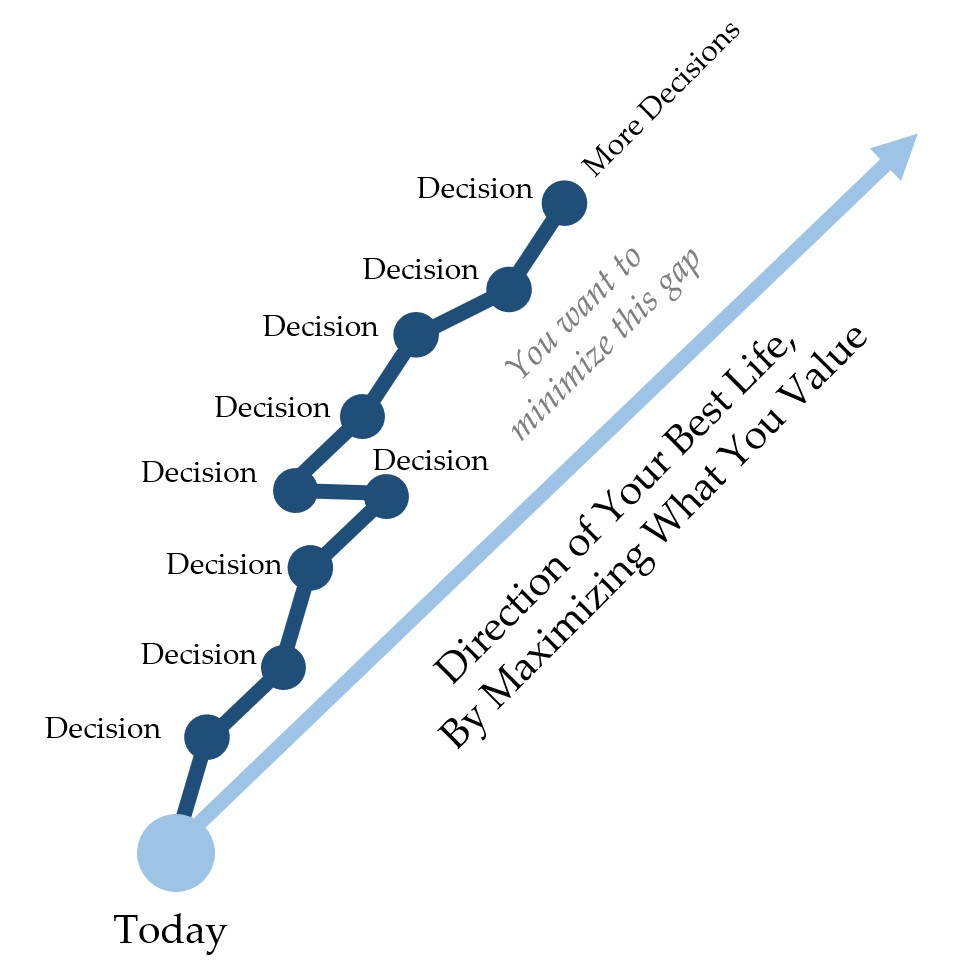

One way to visualize what applying this framework is intended to do is with the following visual. Today, you are at some starting point (someone else’s starting point is going to be different). There’s a ray emanating from that starting point, which represents the direction of your best life based on your collective values. Specifically, this a ray (without a specified end or destination), but rather a general direction. The ray’s direction changes when your values do, but it’s unlikely that occurs very frequently. Every day you are making hundreds of decisions, each of which moves you in some direction. Some of those are pretty closely aligned with the ray, some less so; sometimes you make a really “bad” decision (meaning it is the opposite direction as the ray).

If you want the best life you can have, you want to come up with a system that helps you as consistently as possible make decisions that align with the direction of this ray, while taking into account the limited resources (time and energy) that you have. You want to grow yourself into being a person whose decisions are aligned with the ray. The steps to do that are thus: 1) understand what direction your ray is in (identify and wrestle with what you value), and then 2) set up a system that is efficient with your limited energy and time that lets you make decisions that align with your values.

When To Do It

People typically use New Year’s Eve as the date for setting goals, but that is simply because it serves as a convenient rallying point. There is no reason that has to be the case. If you have never undertaken a deep value-exploration exercise like this, the best time to start is now. Waiting doesn’t mean you don’t have things you value, it just means that you have not specifically identified them and wrestled with how they reconcile together. The approach outlined here is about nailing down those values and a subsequent continuously evolving personal growth journey to help you align your life with them. As a result, there is not a specific time of year or life where you can or cannot do this. There is no reason you need to do it at the beginning of a new year, but of course that is a great time to do it (as is any).

Time Commitment

The first time you put this into practice, it will take several hours; you may want to spread it out over a few sitting periods so your brain can think in-between them. You’ll find that most of that time is spent thinking through what your real values are and grappling with how to reconcile across them13. You also are developing a new muscle going up and down the elevator and thinking about how things tie together. In subsequent years, this takes far less time because you are creating an updated version starting with the prior year’s baseline, stacking growth year over year.

Where To Start

The most effective way to start is to take any existing list of “goals” you have or that come to mind; then, push them into the three categories (values, goals, actions-discrete/habit).

From there, pick one of them and ask yourself “why it matters” and “how you can go about accomplishing it” (use the abstraction elevator) – after a few times going up and down and expanding at each layer, you will likely be on your way. Write your answers down. Refer back to the descriptions and examples in this document if you are stuck; there are additional tips below as well for each section.

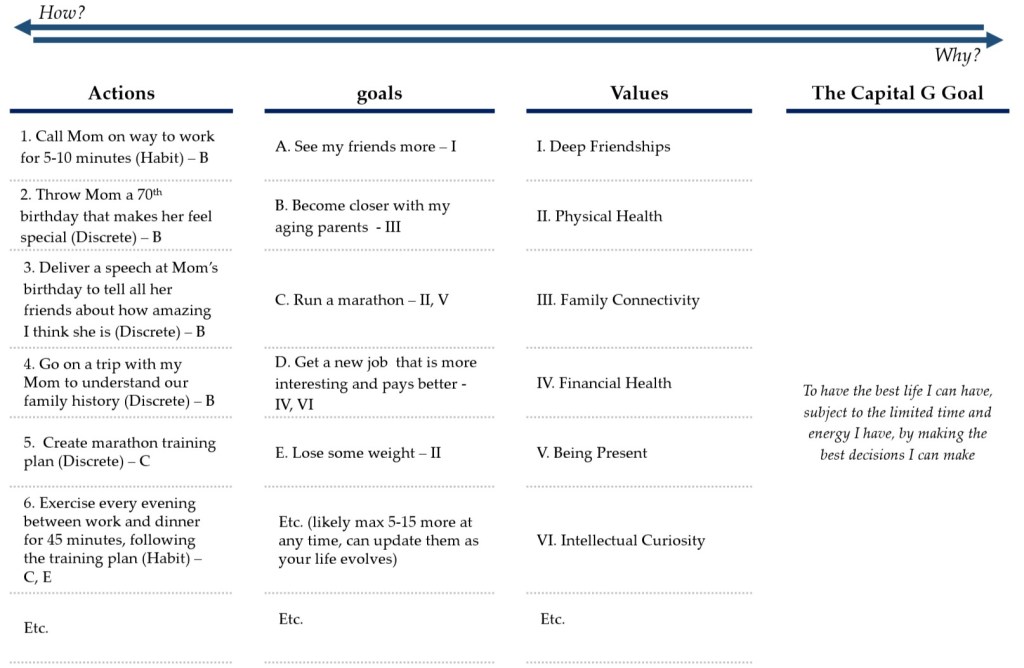

As mentioned, you will want to write down your thoughts as you go through the exercise. The outcome of the exercise is to codify your values, goals, and actions in a table containing three lists. On the left side is Actions (with each labeled as “discrete” or “habit”), the middle contains Goals, and the Right contains Values. It may make sense to label each row (using numbers for Actions, letters for Goals, and roman numerals for Values) so that you can identify which goals support which values, etc.

The reason you want to record your thoughts in a final written output is that a substantial part of the benefit you gain from this framework is from your deep engagement with the initial exercise of codifying your thoughts. The initial exercise forces you to reconcile across the different things you care about and arrive at a unified way those values relate to and harmonize with each other, and how they translate into your goals and targeted actions. By increasing the saliency of your values and forcing you to connect key actions and goals to those values, your brain receives a power-up for its ability to make decisions aligned with your values – even if you never look at the sheet again.

An example of what a final output looks like using the examples from this post is:

Tips For Applying This Framework

Values: Getting your values to truly capture what you value is the most important item. Stare long and hard at them. A good way to come up with your values is to think back on big decisions and why you made them – what dimensions or criteria were you most focus on and why? Think college, jobs, spouse, moving, big purchases – things that were the most likely to have awoken your most thoughtful thinking. It’s likely a list of 5-10 things, at most.

goals: If a goal doesn’t support at least one value (great if you have goals that support more than one), then you may want to question how much of a priority it is. You will find that there are some things you thought of as goals that don’t really help align the way you live with the values you have; given your limited time and energy, these are likely the first contenders to be deprioritized or eliminated. Every person has a different number of goals they can support based on their personal time and energy limits, but many people have more goals than they can actually accomplish.

Habits: Habits deserve a lot of attention. As noted above, forming habits that are aligned with your values is like getting superman on your team helping you align the way you live with what you want given the time and energy hacking capabilities they possess. Having habits that are not aligned with your values, on the other hand, will mean you are battling superman every day on your journey to have the best life you can. It’s worth taking a few minutes to specifically take an inventory of any habits that you think may not be aligned with your values. In fact, whatever the thing is that came to your mind as you read that last sentence is likely the first habit on the chopping block to work on breaking.

Discrete Actions: This is in ways the most obvious category: “give a great speech for my Mom’s 70th birthday”. The biggest risk is not specifying them correctly and falling victim to what Tim Urban very accurately has dubbed the “Procrastination Monkey”. Assigning dates to things can help you avoid this issue (and perhaps can help you avoid skipping the bar with friends for a late night of last-minute speech writing).

Metrics: This is not a layer itself, and as a result was not discussed in the framework above. Some people find quantification and tracking to be helpful. If that sounds like you, tying metrics to actions or habits may be helpful. Be careful about the risk of losing your ability to be present.

What To Do After You Have Your Draft Complete

It likely makes sense to have some regular period where you sit down for an hour to re-read what you wrote down from this exercise – not so often that you use too much time on it, but frequently enough that it is becoming increasingly engrained as your operating system; perhaps once a quarter or once a month. You can then update it once a year or once a quarter as needed. During those updates, first revisit your values – do these still reflect what you most care about? Did you not quite capture it right the first time? What needs tweaking or refining? Your goals are more tangible versions of those values, manifestations of them for your current circumstances, time, and place; as you grow, you should expect that goals will continuously roll off your list and be replaced by new ones. Your actions are meant to support these goals and values, helping guide your decisions to align with your values, and thus your updated goals and values require updated actions. For all the reasons previously discussed, it is particularly important to pay attention to current and potential new habits, to ensure they are aligned with your values. After some period of time (perhaps a year) of putting this into practice, you may be shocked by how much closer your life can be to what you want it to be if you look back to a year earlier.

- This post attempts to minimize the number of assumptions needed and derive as many conclusions as possible through logical thinking. One of the assumptions underpinning the entire post, however, is that you do want the best life you can have ↩︎

- See “Time Density” for more on the inequality of minutes / non-linear nature of the human experience of time ↩︎

- See “Interestingness as an Energy Hack” ↩︎

- Uncontrollable factors include environment, birth/genetics, upbringing, etc.; these are inputs, and not things that you can control ↩︎

- See “Money” for more on how money currently serves as the best available technology to convert between time and energy ↩︎

- See “You’re Either Growing or Dying: Do Things That Compound” for more on this, but it is worth noting that compounding is a powerful hack on energy utilization ↩︎

- See “Types of Thinking” for more on the System 1 and System 2 thinking framework; this heavily intersects with the basis of this post; in summary, System 1 thinking is quick and instinctive / habitual, while System 2 thinking is deliberate and methodical; there is a tradeoff of accuracy/quality with energy and time usage between these systems ↩︎

- See “What We Can Borrow from Businesses Management” for more on the general ways that markets have pushed businesses to develop tools that can also be leveraged in the personal domain ↩︎

- See “Judgement” for more; the capability of making decisions that lead to your desired outcome is “Judgement” ↩︎

- See “Types of Thinking” and “You’re Either Growing or Dying: Do Things That Compound” ↩︎

- See “Time Density” for more on the inequality of minutes / non-linear nature of the human experience of time ↩︎

- See Patrick O’Shaughnessy’s “Growth over Goals’” for an excellent discussion around the tension between these terms, ↩︎

- This is not a net use of time; rather, it is time that you’re really just pulling forward – if you don’t wrestle with and reconcile your values now on purpose at your own election, you will likely eventually be forced to due to some external circumstance at a time of their choosing ↩︎

Leave a comment